Primary Survey

The goal of the Primary Survey is to identify and immediately treat life threatening injuries.

These injuries should be actively looked for and excluded:

- Airway Obstruction

- Tension Pneumothorax

- Open Pneumothorax

- Massive haemorrhage

- Haemothorax

- Flail Chest and pulmonary contusion

- Cardiac Tamponade

Due to the importance of simultaneous assessment and treatment in the care of the acute trauma patient, the principles of Damage Control Resuscitation are included here.

The principles of management after the resuscitation bay are covered at Damage Control Surgery.

Process

The primary survey follows the CABCD approach:

- Safe approach

- Catastrophic haemorrhage

- Airway

- Breathing

- Circulation

- Disability

Safe Approach

Ensure you can safely access the patient.

Catastrophic Haemorrhage

Prevent exsanguination.

Assessment:

Audible bleeding indicates catastrophic haemorrhage.

- Identify immediately life threatening bleeds

Typically extremity haemorrhage.

Management:

- Direct Pressure

- Direct Pressure (more)

- Indirect Pressure

To artery proximal to injury. - Tourniquets

- Consider:

- Wound packing

- Haemostatic agents

Airway

Restore airway patency.

Assessment:

- Rapid Assessment:

Ask the patient to:- Identify themselves and what happened

This indicates airway patency, adequate breathing, conscious state. - Open their mouth

- Take two deep breaths

- Cough

- Ask: “Does your breathing feel normal?”

If the above are normal, then the chance of a serious breathing problem is unlikely. - Ask: “Where do you hurt?”

- Ask: “Where else do you hurt?”

- Identify themselves and what happened

- Check for threatened airway:

- Unconsciousness/obtundation

Loss of airway reflexes. - Patency

- Look for obstruction or foreign body

- Listen for stridor, gurgling, abnormal phonation

- Consider:

- Facial, mandibular, tracheal, or laryngeal fractures

- Unconsciousness/obtundation

Management:

Head tilt is contraindicated in spinal injury; mandibular manipulations are safe and probably more effective.

- Basic airway manoeuvres

- Chin lift

- Jaw thrust

- Place OPA

- Consider NPA

Relatively contraindicated if concern for base of skull fractures. - Intubate

Considerations:- Patient, team, and environment are optimised

Roles assigned (including MILS. - SpO2 <93%

- GCS <8

- Patient, team, and environment are optimised

Breathing

Ensure adequate oxygenation.

Assessment:

Mnemonic for respiratory assessment is RU IN SHAPE.

- Respiratory Rate

Significant when:- RR >20

- RR <8

- Unequal movements

- Injuries

Major thoracic trauma. - Search

- Hands on

Palpate. - Auscultate

- Percuss

- (Everywhere)

If no signs of life, commence traumatic cardiac arrest management.

Management:

Breathing interventions follow a basic respiratory support ladder.

- Rescue

If entrapped. - Optimise positioning

- Splinting of flail segments

- Oxygen

- Analgesia

- NIV

- Decompression

- RSI

- ↑ FiO2

- PEEP

- Recruitment

- Proning

Circulation

- Actively look for and control sources of bleeding

- Maintain perfusion at the minimum viable for life

- Resuscitation with blood

- Minimise crystalloid and vasopressor use

Assessment:

Central capillary return is used due to:

- Centralisation of blood volume

- Hypothermia of extremities

- Perfusion

- GCS

- Capillary return

Central >3 seconds. - Pulse

Key makers.- Present

- >120

- Look for bleeding

Sources are SCALPER:- Scalp

- Chest

- Abdomen

- Pain on palpation away from bruises

- Fat fractures suggest high risk of hollow organ injury

Divet felt under intact skin.

- Long Bones

- Pelvis

- Pain suggests pelvic injury

- External

“The Floor.” - Retroperitoneum

Management:

- Permissive hypotension

Accepting degree of hypotension in order to ↓ bleeding and allow clot to form, whilst maintaining some semblance of organ perfusion. Target is a balance of risk of bleeding versus malperfusion, and varies with pathology:- Traumatic brain injury:

- <50: SBP >110

- 50-69: SBP >100

- >70: SBP >110

- Spinal injury: MAP >85mmHg

- Blunt trauma: >80mmHg or radial pulse

- Penetrating trauma: >60mmHg or conscious

- Traumatic brain injury:

- Fluid/blood resuscitation

- In-line warmers should be used to minimise hypothermia

- Massive transfusion protocol if major bleeding

- Chest decompression

- Haemopneumothoraces should be treated initially with a finger thoracostomy

- Formalisation with a chest drain should occur when clinically appropriate

A separate site may be required for drain insertion, depending on sterility of the initial thoracostomy. - These should be occluded with a one-way valve to prevent lung collapse in the negatively-pressure ventilated patient

- Formalisation with a chest drain should occur when clinically appropriate

- This may be performed empirically in the unstable patient

- Haemopneumothoraces should be treated initially with a finger thoracostomy

- Resuscitative thoracotomy

Blood product in a matched ratio should be used, however there are times when this is not immediately available. Crystalloid is permissible to maintain the minimum viable blood pressure until blood product arrives.

Resuscitative thoracotomy is covered under Resuscitative Thoracotomy.

Indications include:

- Penetrating trauma with cardiac arrest <10 minutes

- Blunt trauma with witnessed cardiac arrest

- Can be considered in patients with cardiac arrest <10 minutes, with much lower likelihood of success.

- Refractory shock with echocardiographic pericardial collection and other causes of traumatic arrest addressed, i.e.:

- Intubated

- Bilateral thoracostomies

- Aggressive blood product resuscitation

Disability

Identify a neurosurgical injury that requires immediate intervention.

Assessment:

- GCS

- Pupillary size and reaction

- Focal defect

- Spinal Cord Injury level

Management:

Management of TBI is covered under Traumatic Brain Injury.

- Correct hypoxia

- Maintain cerebral perfusion

- Consider emergency burr hole if:

- Lateralising neurology

- ↓ Conscious state

- No CT scan available

- No neurosurgeon available

Exposure

- Identify potential missed injuries; particularly on the back

- Prevent hypothermia

Assessment:

- Completely undress

- Logroll

- Cover and rewarm

Adjuncts to the Primary Survey

Monitoring:

- Capnography

Confirm ETT position. - ECG

- Dysrhythmias/ST segment changes

May indicate blunt cardiac injury or causative event (e.g. MI leading to MVC).

- Dysrhythmias/ST segment changes

Interventions:

- IDC

- Consider filling bladder to tamponade pelvic venous bleeds

- Avoid if suspecting urethral injury

- Blood at urinary meatus

- Fractured pelvis

Investigations

Bedside:

- Ultrasound

FAST scanning:- Free fluid in abdomen

To indicate whether a hypotensive patient should proceed immediately for laparotomy (with a positive FAST). A normotensive patient with a positive FAST should proceed to CT, in order to aid surgical planning. - Pneumothorax in chest

- Free fluid in abdomen

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage is a bedside test to evaluate presence of abdominal haemorrhage.

10mL/kg or 1L of saline is infused into the peritoneal cavity via a small midline incision to determine need for laparotomy. It is superseded by ultrasound, but has niche uses in the morbidly obese or subcutaneously emphysematous hypotensive patient who is at risk of transport for a negative CT.

Laboratory:

- Bloods

- Group and Cross-match

6 units for major trauma. - FBE

- Coag

- Group and Cross-match

Imaging:

- CXR

- Pelvic XR

Key Studies

Viscoelastic Testing:

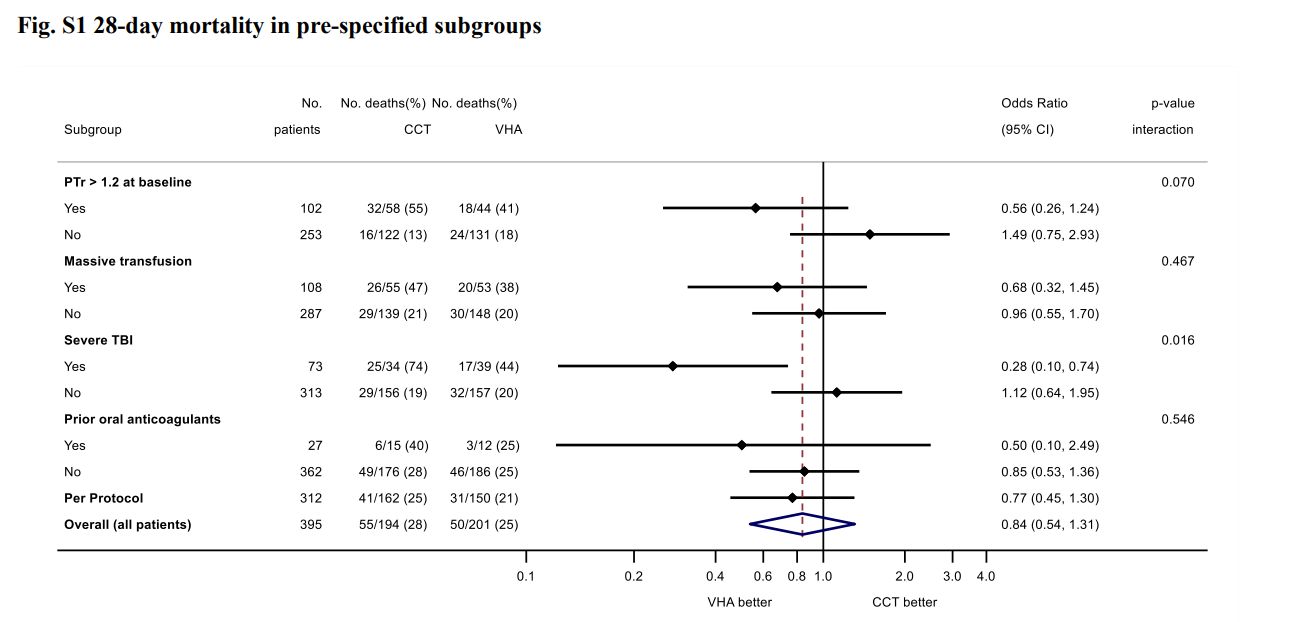

- ITACTIC (2020)

- 392 adult Europeans with trauma requiring MTP activation and active bleeding within 1 hour of ED admission and 3 hours of injury

- Block randomised multicentre (7), clinician unblinded, researcher blinded RCT

- 392 patients provides 80% for 15% ↓ in death or massive transfusion at 24 hours

- Viscoelastic assays (ROTEM or TEG) vs. conventional coagulation testing

- Protocolised treatment of coagulation abnormalities for both groups

- All patients received 1:1:1 transfusion, with algorithmic administration of TXA, fibrinogen, and additiojnal products

- Most patients severely injured

- No difference in primary outcome (67% vs 64%)

Ambitious difference for a monitoring trial. - Secondary outcome supports 28 day mortality ↓ in TBI group

References

- Bersten, A. D., & Handy, J. M. (2018). Oh’s Intensive Care Manual. Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.