Unexpected Difficult Airway

- All airway techniques fail

- Repeated attempts at tracheal intubation ↑ risk of CICO, death, and brain damage

- Most airway complications are unexpected

- CICO events are rare but result in high anaesthetic mortality

- CICO mortality and morbidity occurs due to delay in performing FONA, not due to the procedure

- A standardised approach improves crisis performance

- Cognitive and motor skills are significantly impaired in a crisis

- Priority is to maintain:

- Oxygenation

- Ventilation

Difficult Airway Drill

This section is taken from the DAS 2015 guidelines.

- Plan A

Mask ventilation and intubation.- Optimise as many factors as possible prior to induction

- Plan B

Maintain oxygenation with SAD.- Use 2nd generation device

Higher sealing pressures, gastric port. - Up to 3 attempts with different devices/sizes

- If successful, consider:

- Waking

- Intubate through SAD

Using fibreoptic and aintree catheter. - Continue with SAD

- FONA

- A failure of two techniques (e.g. intubation and SAD) should prompt preparation for FONA

- Use 2nd generation device

- Plan C

Maintain oxgenation with face-mask ventilation (if possible).- 2-person technique

- Use adjuncts (OPA, NPA)

- Consider fully paralysing the patient if face-mask ventilation is not possible and critical hypoxia is not reached

- If successful:

- Wake if able

- FONA if definitive airway required immediately

- Plan D

Declare that “This is a CICO situation”. Proceed to emergency FONA.- Scalpel cricothyrotomy

- Needle cricothryotomy

- Jet ventilation

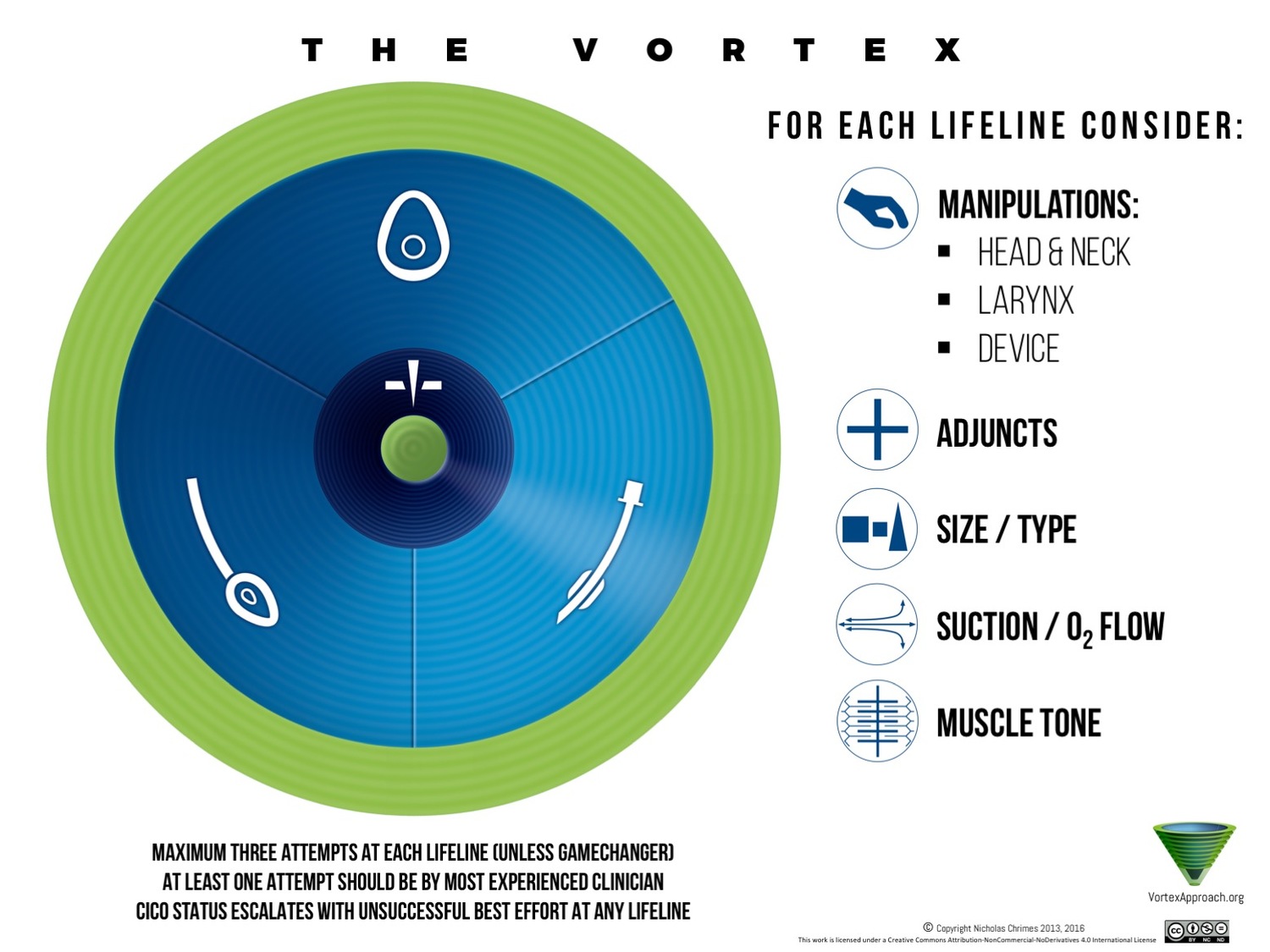

The Vortex Approach

This section describes a complemenatry tool to use when managing the unanticipated difficult airway

The vortex approach recognises the fact that:

- CICO scenarios are a high-stress event that causes cognitive overload

Cognitive biases abound, with impaired decision-making, fixation, omissions being common.- Complicated guidelines are hard to follow in such situations

- Surgical airway techniques are psychlogically confronting

- Existing guidelines focus on clinical content rather than human factors

Principles of the vortex approach:

- There are three ‘non-surgical’ airway management options

Though there are many different airway management techniques, most are not applicable in the unexpected airway emergency. Reducing the number of emergency tools encourages clinicians to become proficient with a limited number of devices.- BMV

- SGA

- ETT

- If a ‘best effort’ at any of these three lifelines is unsuccessful, another should be attempted

‘Best effort’ and ‘reasonable number of attempts’ are a context-dependent decision.- A failure of any technique is a ‘spinal inwards’ towards the centre

Emphasises:- Diminishing time and options available as successive techniques fail

- If oxygenation cannot be achieved with a non-surgical technique, FONA must be performed

- Ability to oxygenate/ventilate results in movement outwards towards the ‘green zone’

This position of relative safety should prompt:- Reoxygenation

Optimise SpO2 and re-establish FRC. - Assembling additional resources

- Personnel

- Equipment

- Location

- Make a plan:

- Maintain the current lifeline

- Convert the lifeline to a preferred technique

- Perform a semi-elective tracheostomy

- Convert an LMA to an ETT via use of an Aintree catheter

- Optimise the current technique to re-attempt the primary technique

- Reoxygenation

- A failure of any technique is a ‘spinal inwards’ towards the centre

Equipment

As difficult airways are often unpredictable, emergency airway equipment should be available wherever airways are managed. This equipment should be:

- Clearly labelled

- Stored in a:

- Dedicated container

- Known location

Staff should be orientated to its location, and a process of orientating new staff exist.

- Portable

- Rapidly available within 60 seconds

In the OR, operating suite, or off-the floor.- Supplementary equipment should be available within 5 minutes

- Compliant with:

- Sterility standards

- Checked daily and replenished when required

- Checked every 3 months for battery function

- Restocked and resealed promptly after use

Adult Equipment

Includes:

- Airway adjuncts

- Oropharyngeal airways size 3, 4, 5 and 6

- Nasopharyngeal airways size 6, 7 and 8

- Laryngoscopes

- Macintosh blades size 3 and 4

- Alternative blades

- Two laryngoscope handles

Including one stubby handle.

- ETT adjuncts

- ETT introducer with a Coudé tip

e.g. Frova. - Malleable stylet

- Selection of specialised ETTs

- MLTs

- Reinforced tubes

- Flexible tubes appropriate for fibre-optic intubation

- Parker Flexi-tip

- iLMA flexible tube

- Airway exchange catheter

- ETT introducer with a Coudé tip

- LMAs

- Intubating LMAs

- LMAS size 3, 4, and 5

Able to admit a bronchoscope.

- Emergency airway equipment

- Surgical cricothyrotomy kit

Containing:- Scalpel with #10 or #20 blade

- Tracheal hook

- Trousseau dilator

- Tracheostomy tubes size 6 and 7

- Catheter cricothyrotomy kit

Containing:- Cannula

- Pressure or flow regulated insufflation system

- Surgical cricothyrotomy kit

- Oesophageal intubation detector

- Immediate CO2 detector

Capnograph, capnometer, or calorimetric detector.

Paediatric Equipment

Should be available wherever paediatric airways are managed:

- Airway adjuncts

- Oropharyngeal airways 000, 00, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

- Nasopharyngeal airways 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5

- Laryngoscopes

- Macintosh blade size 1

- Straight blades

e.g. Miller sizes 0, 1, 2.

- ETT adjuncts

- Paediatric introducers

- Malleable stylets

- Cuffed and uncuffed ETTs in various sizes

2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 5.5. - Airway exchange catheters

Size 8 Fr, 11 Fr, and 14 Fr.

- LMAs

- LMAs size 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5

- Emergency airway equipment

- Paediatric cricothyrotomy set, size 3.5mm

- Kink-resistant transtracheal catheter

- High pressure, pressure or flow-regulated ventilation system

- Oesophageal intubation detector

- Immediate CO2 detector

Capnograph, capnometer, or calorimetric detector.

Additionally, specialist paediatric units should have:

- Ultra-thin flexible intubating bronchoscope

Bronchoscopes

Should be available within 5 minutes to support the above. Bronchoscopic equipment should include:

- Intubating catheter

e.g. Aintree. - Spare battery

- Intubating airways

- Endoscopy masks

- Bronchoscopic swivel connectors

- Wires

- Anti-fog solution

- Local anaesthetics

Including:- Sprays

- Atomisers

- Jelly

- Nasal vasoconstrictor

- Bite block

Supplementary Equipment

Optional equipment may include:

- Double-lumen airway

e.g. Combitube. - Non-standard laryngoscope blades

- McCoy

- Flexiblade

- McMorrow

- Video laryngoscopes

- Including hyper-angulated blades

- Airway stylets

- Light wand

- Equipment for retrograde intubation

- Rigid ventilating bronchoscope

Grab-Bag

Bag containing essential equipment that can be taken to emergency locations. Recommended content:

- Airway adjuncts

- OPAs

Size 3, 4, 5. - NPAs

Size 6, 7, 8.

- OPAs

- LMAs

- Intubating LMAs

Size 3, 4, 5; with dedicated tubes.

- Intubating LMAs

- ETTs

- ETTs

Size 5, 6. - Intubating stylets

- Macintosh blades

Size 2, 3, 4. - Straight blade

Size 3. - Two laryngoscope handles

- Swivel bronchoscopy connector

- ETTs

- CO2 detector device

- Emergency surgical airway set

References

- Frerk, C., Mitchell, V. S., McNarry, A. F., Mendonca, C., Bhagrath, R., Patel, A., … Ahmad, I. (2015, December 1). Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aev371

- ANZCA. PS 61: Guidelines for the Management of Evolving Airway Obstruction: Transition to the Can’t Intubate Can’t Oxygenate Airway Emergency. 2016.

- T. M. Cook, S. R. MacDougall-Davis; Complications and failure of airway management, BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia, Volume 109, Issue suppl_1, 1 December 2012, Pages i68–i85, https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aes393

- Chrimes, N. The Vortex: A Universal ‘High-Acuity Implementation Tool’ for Emergency Airway Management. Br J Anaesth 117 Suppl 1, i20-i27. 2016 Jul 20.

- Chrimes, N. Fritz, P. The Votex Approach: Management of the Unanticipated Difficult Airway. Smashwords. 2013.

- ANZCA. PS56: Guidelines on Equipment to Manage a Difficult Airway During Anaesthesia.