Spinal Cord Injury

Spinal cord injuries are classified:

This covers classification and management of acute spinal cord injuries, management of a patient with a chronic spinal cord injury are covered under Chronic Spinal Cord Injury.

- Clinically by:

- Level

Lowest segment with:- Antigravity motor function

- Normal sensory function

- Degree

- Complete

No sensory or motor function in the S4-S5; i.e. no voluntary anal contraction or perianal sensation. - Sensory Incomplete

- Sensory function preserved below level of the lesion

- No motor function preserved more than 3 levels below the motor level

- Motor Incomplete

Motor function preserved below the neurological level.

- Complete

- Level

- Radiographically by stability

Specific nomenclature includes:

- Tetraplegia

Motor or sensory dysfunction of the upper and lower limbs due to injury to the cervical cord . - Paraplegia

Motor or sensory dysfunction of the lower limbs due to thoracic, lumbar, or sacral cord injury. Includes cauda equina and conus medullaris injury. - Zone of Partial Preservation

Spinal segments below the injury that have preserved motor or sensory function.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Associated with:

- Males

- Young

- Blunt trauma

- VA

- Falls

- Sports-related injuries

- Spinal fractures

20% of patients will have an associated cord injury. - Head injury

2-10%; more common with mores severe head injuries.

Pathophysiology

The spinal cord:

- Extends from the foramen magnum to the L1-L2 level in adults

- Ventral and dorsal roots exist at each intervertebral level

- Cauda equina refers to the lumbo-sacral nerve segments that continue below the spinal cord

Less susceptible to injury due to the larger lumbar canal size.

- Provides sympathetic supply from T1-L2

- Provides parasympathetic supply from S2-S4

Parasympathetic supply to everything but the pelvic viscera is supplied by the vagus nerve.

Spinal cord injury is biphasic, and is divided into:

- Primary injury

Mechanical injury leading to focal injury to the cord via:- Compression

Haematoma. - Traction

- Laceration

- Ischaemia

Via spinal arterial injury.

- Compression

- Secondary injury

Local ischaemia extending from the site of injury, leading to haemorrhage into the cord and ultimately neuronal necrosis.

Aetiology

Clinical Features

Beware the rising lesion: An ↑ in spinal cord injury level occurring with spinal cord oedema, which may precipitate respiratory failure.

Below the lesion there is a:

- Loss of efferent pathways:

- Weakness

- Hypotonia

- Loss of afferent pathways:

- Areflexia

- ↓ Sensation

- Loss of autonomic (sympathetic) tone:

- Vasodilatation

- Bradycardia

- Priapism

- Urinary retention

- Paralytic ileus

Paradoxical breathing occurs when the diaphragm contracts in absence of chest wall tone, resulting in a paradoxical in-drawing of the chest during inspiration.

Spinal Syndromes

In addition to the general features described above, spinal cord injury can present with constellations of specific features.

Spinal Shock:

- Altered physiological state that:

- Occurs immediately following injury

- May persist for between 48 hours to several weeks

- Resolves gradually

- Involves lower motor neuron dysfunction distal to the injury:

- Flaccid paralysis

- Hyporeflexia

- Anaesthesia

- Incontinence

Neurogenic shock:

Shock is covered in detail under Shock.

- Distributive shock due to loss of sympathetic tone

- May occur within 30 minutes after injury and last up to 6 weeks

- Features include:

- Hypotension

Significant orthostatic component. - Bradycardia

- Hypothermia

- Hypotension

Central Cord Syndrome:

- Motor and sensory dysfunction greater in the arms than the legs

- Due to injury of the centre cord

Cervical segment affected due to location of cervical spinal tracts. - Typically due to hyperextension with pre-existing spinal canal stenosis

Anterior Cord Syndrome:

Anterior cord syndrome is most common after aortic pathology or surgery.

- Loss of motor, pain, and temperature sensation

- Preservation of fine touch and proprioception

- Due to interruption of blood supply to anterior spinal cord

Brown-Séquard Syndrome:

Brown-Séquard Syndrome is vanishingly rare but remains a favourite of anatomists and examiners.

- Ipsilateral loss of motor, proprioception, and fine touch below the level of the lesion

- Contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation ~1-2 levels below the lesion

- Due to penetrating injury to a transverse half of the spinal cord

Conus medullaris Syndrome:

- Genitourinary dysfunction:

- Flacid paralysis of external anal sphincter

- Faecal incontinence

- Overflow urinary incontinence

- Impotence

- Perianal anaesthesia

- Due to T12-L1 injury

Cauda equina Syndrome:

- Constellation of:

- Asymmetrical lower limb weakness

Predominantly LMN. - Sensory loss in the affected motor distribution

- Bladder and bowel areflexia

- Asymmetrical lower limb weakness

- Due to injury to lumbosacral nerve roots below L1

Injury at the thoracolumbar junction may affect both the conus medullaris and the cauda equina, resulting in features of both syndromes.

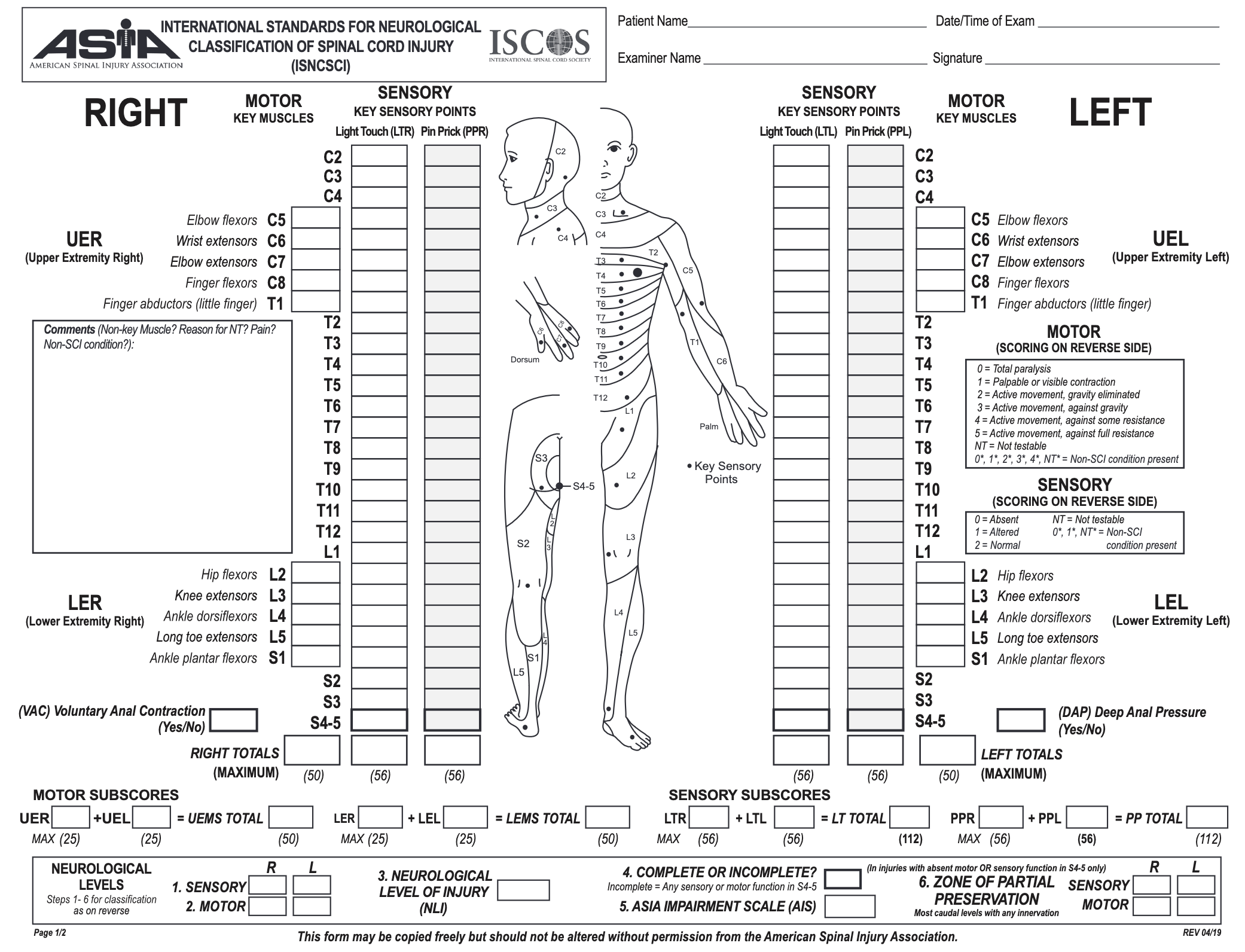

ASIA Impairment Scale

The American Spinal Injury Association impairment scale:

| Grade | Movement |

|---|---|

| 0 | Paralysis |

| 1 | Palpable or visible contraction |

| 2 | Movement with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Antigravity movement |

| 4 | Movement against moderate resistance Additional (subjective) nuance can be documented by using 4+ or 4- for varying levels of “some” resistance. |

| 5 | Movement against full resistance |

| 5* | Expected movement against full resistance if inhibiting factors (pain, myopathy) were not contributing |

| NT | Not testable e.g. Due to immobilisation, pain, amputation, or contractures. |

- Is the most validated injury for diagnosis and classification of spinal cord injury

- Can predict long-term motor outcome from initial exam

- Involves determining:

- Sensory level for the each side using light touch and pin-prick sensation

- Motor level for each side

- Determine the neurological level

This is the most cephalad of the levels determined in steps 1 and 2, i.e. the level where abnormality begins. - Completeness

Presence or absence of sacral sparing, indicated by:- Anal contraction

- Perianal sensation

- Grade

- A: Complete injury

- B: Sensory incomplete

- C: Motor incomplete and >50% of key muscle functions below the neurological level are ⩾3/5

- D: Motor incomplete and <50% of key muscle functions below the neurological level are ⩾3/5

- E: Normal

Diagnostic Approach and DDx

Clinical assessment determines the need for:

- Immobilisation

- Imaging

Ruling-out the need for imaging is performed with one of two assessments:- NEXUS

- Canadian C-Spine rule

Both NEXUS and the Canadian rules are highly sensitive, which is critical to avoid missing potentially significant lesions.

NEXUS

Imaging is not needed if all of the following criteria are met:

- No posterior midline cervical tenderness

- No intoxication

- No focal neurology

- No painful distracting injury

- Normal alertness

Adequate three object recall at 5 minutes.

Investigations

- All patients not cleared on a clinical decision rule should have high-resolution multidetector row CT of the full spine, with an experienced practitioner reporting the images

- If concern despite normal CT → MRI

e.g. Neurological deficit, high risk injury, CT abnormalities such as osteophytes that may cloud interpretation.

Imaging:

Plain radiographs no longer have any role in evaluating a suspected spinal cord injury. Historical approaches include:

- Plain imaging

Sensitivity ~50%.- A-P

- Lateral

- Odontoid peg

- Dynamic studies

Flexion-extension views.

- CT

- Highly sensitive

- May miss significant unstable ligamentous injuries that occur without bony involvement

- Highly sensitive

- MRI

Superior imaging of spinal cord and soft tissue, including unstable ligamentous injuries.

Management

- Avoid secondary injury by preventing cord ischaemia and further dislodgement

- Early fixation:

- Improves neurorecovery by ↓ secondary injury in incomplete injury

- Permit immediate rehabilitation and improves overall outcome, but not neurology, in complete injury

Resuscitation:

Principles for airway management are covered below under anaesthetic considerations.

- A

- C-spine immobilisation

- B

- Supplemental oxygen

- VT 6-10mL/kg

- C

- Maintain spinal cord perfusion

- MAP 85-90mmHg

For 72 hours. - Avoid SBP ⩽90mmHg

Native SBP may be 60-80mmHg in context of neurogenic shock. - Blood pressure targets should be maintained for 7 days

- MAP 85-90mmHg

- Bradycardia

May require atropine or pacing; especially with vagal response to intubation.

- Maintain spinal cord perfusion

There is weak evidence that ↑ MAP may improve neurological outcome. This is usually easily achieved, and even one additional functional myotome can have substantial quality of life benefits.

Specific therapy:

- Pharmacological

- Procedural

- Tracheostomy

- C3 or above: Required

- C4: Trial of extubation reasonable, but moderate chance of failure

- C5 or below: Extubation onto NIV has reasonable chance of success

- Operative fixation

Fixation of unstable injuries within 24 hours permits:- Early mobilisation

- Thromboprophylaxis

- Desedation and assessment of:

- Neurological level

- Need for tracheostomy

- Tracheostomy

- Physical

- Chest physiotherapy

Supportive care:

Percutaneous tracheostomy is as safe as surgical tracheostomy in a stable cervical injury.

- A

- Tracheostomy

Required in 20-50%; predictors include:- High level

- Complete injuries above C5 almost always require tracheostomy

- Complete injuries above C3 almost always require mechanical ventilation

- Complete injury

- Thoracic trauma

- Emergency intubation

- High level

- SLT assessment

Especially if anterior fixation.

- Tracheostomy

- B

- Chest physiotherapy

- D

- Psychological support

- E

- Pressure injury prevention

- F

- IDC

- Consider suprapubic catheter

- G

- Stress ulcer prophylaxis

↑ Risk of gastric ulceration. - Bowel care

Stool softeners.

- Stress ulcer prophylaxis

- H

- Thromboprophylaxis

Enoxaparin should be commenced within 72 hours to ↓ VTE risk.

- Thromboprophylaxis

Disposition:

- Transfer to neurotrauma unit

- Early referral to rehabilitation

Airway Management

Intubation considerations:

~75% of spinal cord injury patients require intubation.

- MILS

Reduces amount of cervical spine movement during airway management. MILS:- Involves:

- Stabilisation of the head by an assistant

- Assistant holds the mastoid processes and occiput steady

- May be performed:

- Crouching, standing next to the operator holding to the mastoid processes

- Facing the intubator, holding the occiput and stabilising the neck with the forearms on the chest

- ↑ Rate of failed airway management

- Involves:

- Use airway adjuncts

Use for mask ventilation to reduce:- Requirement for c-spine movement

- Gastric insufflation

- Avoid suxamethonium

- Consider:

- Videolaryngoscopy

At a minimum for all patients with high-thoracic or cervical spine injury.- Permits RSI

- FOI

Reduces amount of cervical spine movement. May be performed awake or asleep.- May be difficult due to blood/secretions

- Awake FOI

- Coughing and gagging may lead to spine movement

May occur either from topicalisation, or if topicalisation inadequate. - Sedation limits post-intubation neurological assessment

- Coughing and gagging may lead to spine movement

- Asleep FOI

- Not using cricoid pressure

May worsen injury.

- Videolaryngoscopy

Extubation considerations:

Extubation failure commonly occurs due to the combination of secretion burden and inadequate coughing, leading to sputum plugging.

- No procedure or imaging requirements in the next 24 hours

- Able to tolerate NIV

- Cuff leak

- Respiratory function:

- No hypoxia

- No significant reversible pathology

- Low secretion burden

- VC >10mL/kg

- Neurological function

- Participation in chest physiotherapy

Marginal and Ineffective Therapies

- Steroids

- Tirilazad

- Naloxone

- Nimodipine

- Induced hypothermia

Anaesthetic Considerations

- A

- Difficult airway due to immobilisation

- B

- High-tidal volume ventilation

10mL/kg prevents atelectasis whilst avoiding high PEEP that displaces the diaphragm to a disadvantageous position.

- High-tidal volume ventilation

- C

- Arterial line

Required if high thoracic injury or above. - Vasoactive support

- Consider vasopressor infusion during induction

- Arterial line

- E

- Suxamethonium is contraindicated 48-72 hours post-injury

Fatal hyperkalaemia may result due to up-regulation of ACh receptors.

- Suxamethonium is contraindicated 48-72 hours post-injury

- G

- Aspiration risk

High risk due to gastric dilation and ↓ emptying.

- Aspiration risk

Complications

Acute complications:

Complications and management of chronic spinal cord injuries are covered under Chronic Spinal Cord Injury.

Respiratory complications are common and occur due to a combination of:

- Respiratory muscular paralysis

- Immobility

- ↑ Secretions

Loss of sympathetic tone.

- B

- Respiratory failure

- Atelectasis

- Bronchospasm

If sympathectomy above T6. - Pneumonia

Mucous plugging. - PE

- C

- Hypotension

- Loss of sympathetic tone below lesion

- Bradycardia (if >T1, causing loss of cardiac sympathetics)

- Bradycardia

- Autonomic dysreflexia

- Hypotension

- E

- Hypothermia

- Vasodilation and excessive heat loss below the injury

- ↓ Ability to shiver

- Hypothermia

- F

- Hyponatraemia

Common, likely due to RAS dysfunction due to reduced renal sympathetic tone. - Urinary retention

- Hyponatraemia

- H

- VTE

Autonomic dysreflexia is covered under Autonomic Dysreflexia.

Prognosis

Reasonable prognostication possible with ASIA Scale:

- ASIA A

- Poorest prognosis

- 7% may reach ASIA B (sensory incomplete) at 1 year

- None reach ASIA C (motor incomplete)

- ASIA B

- 54% reach ASIA C or D at one year

- Much better functional outcomes

- 54% reach ASIA C or D at one year

- ASIA C

- Almost all ambulatory at discharge

- ASIA D

- All ambulatory at discharge

Key Studies

- NASCIS 2

- NASCIS 3

References

- Bersten, A. D., & Handy, J. M. (2018). Oh’s Intensive Care Manual. Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.