Airway Planning

- Oxygenation > Intubation

- Optimise before you compromise

- Consider awake intubation in the presence of predictors of difficult airway

The goal of airway management is to maintain oxygenation and ventilation, without physiological compromise or complications, ideally with a patent and protected airway.

- This does not (necessarily) imply intubation

Oxygen can be delivered by:- Ventilation

- Insufflation

- Apnoeic absorption

- The chosen airway management technique will depend on the patients anatomy and physiological state, the situation, and the indication

- Secondary goals include:

- Airway protection

From aspiration. - Airway security

From dislodgement or obstruction. - Ventilation

For acidosis. - Control of airway pressures

- Control of respiratory timing

- Airway protection

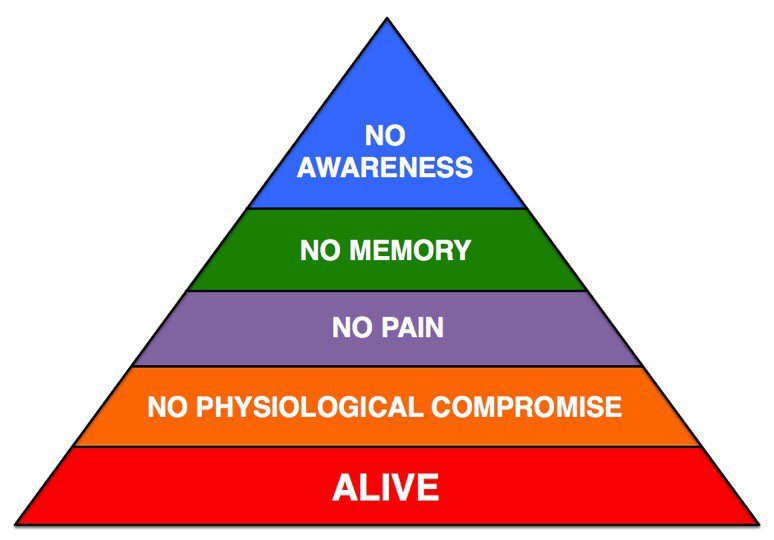

The hierarchy of intubation needs:

Epidemiology of Airway Complications

- The most common cause of airway related death is hypoxia

- Aspiration is the most common cause of airway related anaesthetic death

- Complications from airway management are more common in ED and ICU

- Failed tracheal intubation occurs in:

- ~1/1000-2000 elective cases

- ~1/250 obstetric RSI

- ~1/100 ED intubations

- Failed or difficult tracheal intubation was the primary event in >1/3rd of events

- CICO occurs in ~1/50,000 elective anaesthetics

- CICO is low compared to incidence of difficult intubation

- CICO contributes 25% of anaesthesia-related mortality

- Requirement for emergency FONA ↑ morbidity 15x

- ~25% permanent harm or death

- In 2/3rds of CICO situations, a surgical airway was performed too late to prevent harm

Factors Contributing to Adverse Airway Events

- Human factors

Human failures occur in ~80% of airway events.- Delayed decision to declare failed airway

- Delay in decision to perform cricothyrotomy

- Equipment knowledge

- Training

Especially in surgical airway and rescue techniques. - Poor communication

- Poor teamwork

- Tunnel vision/task focus

- Training

- Systems

- Patient Factors

- Obesity

Important technical factors include:

- Make the first attempt the best attempt

- Subsequent attempts are less successful

- Efficacy of SAD rescue is reduced with more attempts

- Equipment and technique

- Selection of laryngoscopes, and experience in their use

- Bougie

Pre-shaped. - ELM

- Remove cricoid pressure if view is poor

- Call for help early

- Maximum of 3 attempts by a single provider

A Framework for Airway Management

There are many frameworks for airway management. This one aims to:

- Focus on a general plan but not on any specific technique

- Provide an approach that is appropriate for elective anaesthesia as well as emergency airway management

- Plan for and avoid the difficult airway

- In the patient who does not require immediate intubation

- Plan

- Evaluate what techniques are available

Based on the equipment, the patient, and technical skills. Think ACORNS:- Awake

- Waking the patient

- Awake laryngoscopy

- Awake FOI

Is there laryngeal or tracheal pathology?

- Cricoid/FONA

- Scalpel cricothyrotomy

- Needle cricothyrotomy

- Oral

- Mask ventilation

- Intubation

With and without VL.

- Nasal

Is the oral route impossible?- Intubation

Including blind.

- Intubation

- Supraglotic

- Use of LMA

- Use of iLMA

- Awake

- For this patient, consider which techniques are:

- Preferred

Depending on the indication for airway management. In most critical care situations (compared to elective anaesthesia), this will be a definitive oral airway. - Feasible

Could be used to maintain oxygenation +/- ventilation, but may not necessarily be definitive. - Unfeasible

Certain techniques may not be appropriate in certain patients.

- Preferred

- Of this short-list of options, decide on a hierarchy of techniques

Plan for failure and have a series of identified rescue techniques, including a plan for:- Rescue ventilation

Alternate device, e.g. LMA, iLMA. - Rescue intubation

Alternate device.

- Rescue ventilation

- Consider which drugs will be required for these techniques

- Evaluate what techniques are available

- Patient

Adequate patient preparation prior to induction reduces incidence of difficult tracheal intubation. Think PROC:

- Positioning

- Ensure EAM is level with sternal notch to maximise ease of intubation

- Ramping ↑ FRC in the obese patient

- Recruitment

Use of CPAP during preoxygenation prolongs safe apnoea time in obese patients. - Oxygenate

Involves adequate denitrogenation, and consideration of apnoeic oxygenation.- Preoxygenation/denitrogenation

EtO2 > 80% indicates a good proportion of FRC is oxygen, significantly prolonging safe apnoea times from 1-2 minutes up to 8 minutes.- Note that reduced FRC (e.g. atelectasis) will lead to shunt and rapid drop in SpO2 despite a high ETO2 fraction

Significant shunt will result in an SpO2 of < 100% despite adequate ETO2. - This can only be achieved when breathing oxygen through a closed-circuit system

- Note that reduced FRC (e.g. atelectasis) will lead to shunt and rapid drop in SpO2 despite a high ETO2 fraction

- Apnoeic oxygenation

Delivery of oxygen via nasal cannula during the apnoeic period. This technique:- Requires a patent airway

May not help during the apnoeic period when airway tone is reduced. - May be performed with:

- Standard nasal cannula from wall oxygen at 15L.min-1

- Humidified

- May be useful when:

- FRC/ is compromised

- Laryngoscopy is difficult

- Requires a patent airway

- Preoxygenation/denitrogenation

- Perform

- Complete pre-airway management checklist

During pre-oxygenation periods. - Begin!

- Complete pre-airway management checklist

Airway Management Mental Checklist

A good mental checklist should be:

- Easy to remember

Allows it to be used as a ‘challenge-confirm’ checklist - i.e. the steps can be performed by multiple providers simultaneously and then the checklist is used to verify tasks have been completed - Appropriate to be used by a single provider as a ‘call-do-response’ checklist when working with an unfamiliar team

The SPEEDBOMB checklist:

There are many different checklists - I like this one. I routinely perform it during the pause that is provided during pre-oxygenation.

- Suction

- Available

- Consider gastric drainage if NGT is in situ

- Position

In optimal position for this particular technique.- Ear-to-sternal notch

- End-tidal CO2

Available and working. - Equipment

The kit needed for the chosen techniques.- BVM

With mask and PEEP valve. - Airway adjuncts

NPA and OPA available. - Laryngoscope

- Two working laryngoscopes

- Lubricated

Critically ill patients often have high sympathetic tone and a dry oropharynx, making advancement of an unlubricated blade down the tongue difficult. - Appropriate sized blades

- LMA

Lubed and inflated as desired. - ETT

- Of appropriate size

- Lubricated

- At least two, including a smaller one

- If concerned about upper airway pathology/burns, have a size 6 available

- Adjuncts to ETT

- Bougie

Must always be available. - Stylet

- Syringe

For cuff inflation.

- Bougie

- BVM

- Drugs

Including desired dose.- Induction agents

- Muscle relaxant

If concerned, always use adequate doses of a rapid-onset NMBD. - Opioid

- Vasopressors

- Induction agents

- Backup plan

Double check the availability of backup equipment, including FONA equipment. - Oxygen

- Supply present and connected

Ensure that the oxygen tubing attached to the flowmeter is also attached to the patient. - Adequate pre-oxygenation/denitrogenation period

- Use of PEEP for lung recruitment prior to induction

- Supply present and connected

- Monitoring

- ECG

- SpO2

- BP

- Briefing

- Allocate roles

- Detail airway plan A, B, etc

- Declare at what points the airway management strategy will change

e.g. “If the SpO2 falls to less than 93%, I will cease intubation attempts and return to BVM. If unable to mask ventilate, I will place an LMA.”

References

- Nickson, C. The challenge of the critically ill airway. 2018. CIA Course Notes.

- Mommers L, Keogh S. SPEEDBOMB: a simple and rapid checklist for Prehospital Rapid Sequence Induction. Emerg Med Australas. 2015 Apr;27(2):165-8.

- Chrimes, N. Fritz, P. The Votex Approach: Management of the Unanticipated Difficult Airway. Smashwords. 2013.

- Levitan, R. The Airway Cam Guide to Intubation and Practical Emergency Airway Management. 1st Ed. 2004.