Laryngospasm

This is an anaesthetic crisis. Priority is to:

- Break laryngospasm

- Maintain oxygenation

Involuntary contraction of the laryngeal muscles, resulting in closing of the vocal cords and glottic occlusion.

Emergency Management

Immediately:

Cease painful stimulation

Prepare for intubation

Delegate person to assemble drugs and airway equipment.Provide 100% oxygen

Remove airway devices In mild laryngospasm (without total obstruction) it may be reasonable to attempt to break laryngospasm with the LMA in situ.

Provide CPAP 30cmH2O

This aims to stent open the airway.- Typically via face mask

Ensure optimal position, consider use of airway adjuncts. - Deliver low tidal volume ventilation if able via short, sharp squeezes on the bag

Forced inflation will worsen obstruction if there is complete glottic occlusion.

- Typically via face mask

Suction airway

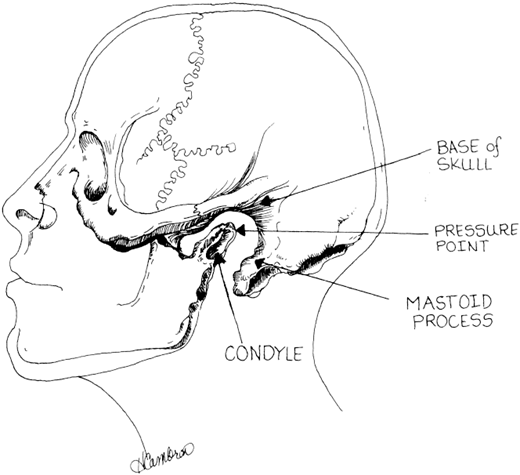

Consider applying painful pressure bilaterally on Larson’s point, which may break laryngospasm

Between mastoid process and posterior edge of mandible, applying pressure anteriorly and medially.

Then:

- If SpO2 >92%, or if desaturation is expected to occur rapidly (obese, children)

Deepen anaesthesia or relax the patient:- Suxamethonium 0.5mg/kg

- Propofol ~20% of induction dose

Effective in ~80% of cases.- Deepens anaesthesia

- Suppresses reflexes

- Overpressure sevoflurane

If airway patent enough to ventilate.

- If SpO2 <92%

Procede directly to intubation:- Suxamethonium 1-2mg/kg

IM is appropriate if an IV route is not available.

- Suxamethonium 1-2mg/kg

Controversial Treatments

Lignocaine has been described to reduce coughing and laryngospasm:

- Evidence is not conclusive

- May ↓ incidence of laryngospasm in at-risk groups

- Not included in many emergency algorithims as its use may delay definitive therapy

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Laryngospasm is common (~9 per 1000 anaesthetics) and is associated with:

- Light anesthesia

On induction and emergence. - Children

Double risk relative to adults (~18/1000 cases), greatest in preschool age groups. - Airway contamination and stimulation:

- ENT surgery

~20/1000 cases. - Oral secretions

Worse with recent URTI. - Blood

- Foreign body

- Aspiration/regurgitaiton/reflux

- Near drowning

- ENT surgery

Pathophysiology

Airway protection is a function of the larynx. The protective nature of the larygneal closure reflex is exaggerated and prolonged in laryngospasm.

Mechanics of laryngospasm can be divided into:

- Inspiratory stridor

Occurs passively due to reduced aductor muscle tone. - Expiratory stridor

Due to active adduction of the cords. - Ball-Valve obstruction

Due to closure of the true cords, the false cords, and the supraglottic tissues.- In this mechanism, positive pressure may worsen obstruction as distension of the pyriform fossae press the aryepiglottic folds more firmly against each other

- Jaw thrust is more effective in correcting obstruction via this mechanism (though paralysis is still often required)

Clinical Manifestations

Laryngospasm should be suspected whenever there is airway obstruction with potential supraglottic cause.

Laryngospasm presents with:

- Stridor

If airway is not completely occluded. - Respiratory distress

- Tachypnoea

- Chest retraction

Due to very negative inspiratory airway pressures.

- Hypoxia

May occur due to:- Impaired ventilation

- Negative pressure pulmonary oedema

- Bradycardia and arrrest

Secondary to hypoxia.

History

Examination

Diagnostic Approach and DDx

Investigations

Management

Post-Emergency Management

Once laryngospasm is broken:

- Consider deflating the stomach with an OGT prior to extubation

- Ensure deep anaesthesia for duration of muscle relaxation

- Ensure extubation only when the patient is fully awake

Prior to extubation, perform an artificial cough:- Single lung inflation with 100% O2 prior to extubation

- Delays desaturation

- Ensures positive pressure in the trachea, which should result in forceful expiration clearing debris from laryngeal inlet

- Single lung inflation with 100% O2 prior to extubation

Complications and Prognosis

Laryngospasm will break with severe hypoxia, but this may only occur after:

- Bradycardia and arrest, and death

- Aspiration

- Pulmonary oedema

Negative pressure pulmonary oedema secondary to inspiratory efforts against a closed glottis.

References

- Padley, AP. Westmead Anaesthetic Manual. 3rd Ed (Revised). 2014. McGraw-Hill Education. Australia.

- Borshoff, DC. The Anaesthetic Crisis Manual. 1st Ed. 2011. Leeuwin Press.

- Larson, PC. Laryngospasm: The Best Treatment. Anesthesiology 11 1998, Vol.89, 1293-1294.

- Salem MR, Crystal GJ, Nimmagadda U. Understanding the Mechanics of Laryngospasm Is Crucial for Proper Treatment. Anesthesiology 8 2012, Vol.117, 441-442.

- Orliaguet GA, Gall O, Savoldelli GL, Couloigner V. Case scenario: perianesthetic management of laryngospasm in children. Anesthesiology. 2012 Feb;116(2):458-71