Shock

Life-threatening state of cellular hypoxia due to globally insufficient delivery or utilisation of oxygen. Shock is generally classified by the aetiology of circulatory disturbance:

This classification maps better to management strategies than aetiology - many pathophysiological processes cause shock via multiple mechanisms; e.g. sepsis causes both distributive and hypovolaemic shock.

- Hypovolaemic

Loss of circulating volume, reducing preload and stroke volume. May be:- Blood loss

- Fluid loss

Can include redistribution due to capillary leak.

- Obstructive

Mechanical obstruction to flow of blood due to compression of:- Great veins, impeding venous return

- Cardiac chambers

- Cardiogenic

Loss of pump function, leading to inadequate cardiac output. - Distributive

Loss of vascular autoregulation, leading to inappropriate allocation of cardiac output. - Dissociative

Loss of oxygen carrying capacity due to:- Profound anaemia

- CO toxicity

- Methaemoglobinaemia

- CN toxicity

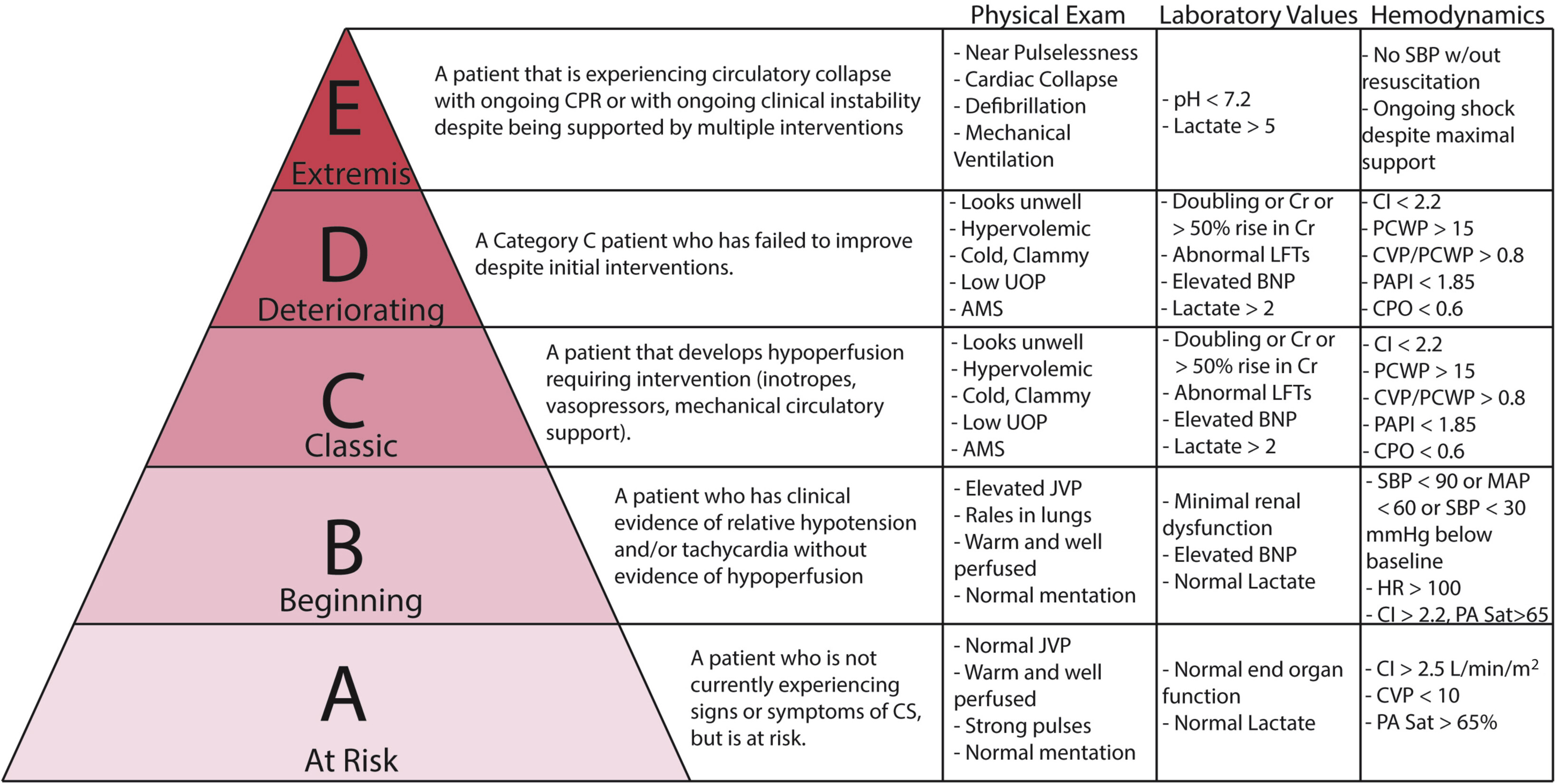

Cardiogenic shock is a point at the far end of the heart failure spectrum. This section provides an approach to shock in general; the specifics of heart failure management, including acute heart failure, are covered in detail under Cardiac Failure.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Pathophysiology

Key pathophysiological concepts in shock include:

- Oxygen delivery

- Dysoxia

Oxygen Delivery

Delivery of oxygen to tissues is a key function of the cardiovascular system, and is given by the following equation:

Practically, oxygen delivery is dependent on three things:

- Cardiac output

- Arterial oxygen saturation

- Haemoglobin

\(DO_2 = CO \times (1.34 \times [Hb] \times SpO_2 + PaO_2 \times 0.003)\), where:

- \(DO_2\) is the delivery of oxygen (mL/min)

Normal DO2 is ~1L/min, whilst normal VO2 is ~250mL/min. - \(CO\) is the Cardiac Output (L/min)

- \([Hb]\) is the arterial haemoglobin concentration (g/L)

- \(SpO_2\) is the arterial oxygen saturation (%)

- \(PaO_2\) is the arterial oxygen partial pressure (mmHg)

The 1.34 in the oxygen delivery equation refers to millilitres of oxygen bound to each gram of haemoglobin.

Dysoxia

Dysoxia occurs when oxygen delivery is inadequate to oxygen demand. Harm from dysoxia is a function of:

- Duration

Limited with rapid correction. - Tissue type

High oxygen demand and extraction organs have poor tolerance to tissue hypoxia.- Hypoxia sensitive:

- Heart

- Brain

- Hypoxia less-sensitive:

- Kidney

- Skin

- Hypoxia sensitive:

Dysoxia can occur when DO2 is apparently adequate, and results from either:

- Failure of cells to utilise available oxygen

Sometimes referenced as histotoxic shock or cytopathic hypoxia. - Intra-organ arteriolar shunting preventing oxygen delivery to the cell, despite adequate organ oxygen delivery

Aetiology

Causes by mechanism include:

- Hypovolaemic

- Blood loss

- Trauma

- Pulmonary haemorrhage

- GIT

- Obstetric

- Retroperitoneal

- Intra-abdominal

- Fluid loss

- GIT losses

- Sweating

- Polyuria

- Pancreatitis

- Burns

- Blood loss

- Obstructive

- Tamponade

- Tension pneumothorax

- PE

- Dynamic obstruction

- Cardiogenic

- Myocardium

- Ischaemia

- Rupture

- Myocarditis

- Contusion

- Myopathy

- Septic

- Drug toxicity

- Ischaemia

- Valvular

- Thrombus

- Chordae rupture

- Arrhythmia

- Bradyarrhythmia

- Tachyarrhythmia

- Myocardium

- Distributive

- Sepsis

- SIRS/MODS

- Anaphylaxis

- Neurogenic

- Adrenal

- Thyroid

- Drug toxicity

Clinical Manifestations

Manifest as failure of end-organ perfusion:

Consider the “4 W’s of Shock”:

- Warm

- Wakeful

- Weeing

- W(l)actate

- Peripheral perfusion

- Temperature

- Mottling

- Capillary return

Central (sternal) is a better marker of organ perfusion and less affected by environmental conditions than peripheral perfusion.

- Altered mental state

Anxiety, confusion, agitation, delirium, drowsiness, coma. - Urine output

Changes in vital signs reflects the extent of circulatory failure:

- ↑ HR

- Early compensatory signs

- May not be present in some conditions

β-blocked, bradyarrhythmias as aetiology.

- ↑ RR

Classically ↑ during evolving shock and ↓ in the pre-terminal phase. - ↓ BP

Sign of significant circulatory failure, usually late onset due to effect of compensatory mechanisms.

Diagnostic Approach and DDx

Investigations

Investigations for adequacy of systemic perfusion include:

- Blood gases

- pH

- Lactate

- Base deficit

- Central venous oxygen saturation

Management

Rapid recognition and treatment are required to prevent irreversible organ dysfunction.

Resuscitation:

- A

- Intubation

- B

- Supplemental oxygen

- C

- Venous access

- Restore organ perfusion

Target MAP ⩾65mmHg:- Exact target may vary depending on other characteristics.

- Volume resuscitation

- Crystalloid

- Albumin

- Blood

- Vasopressors

- Inotropes

- Mechanical support

- Arterial access

- Central venous access if required

Specific therapy:

- Treat precipitating cause

Supportive care:

Disposition:

Marginal and Ineffective Therapies

Anaesthetic Considerations

Complications

Prognosis

Key Studies

References

- Bersten, A. D., & Handy, J. M. (2018). Oh’s Intensive Care Manual. Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.

- Worthley LIG. Shock: A Review of Pathophysiology and Management. Part I. Critical Care and Resuscitation.

- Worthley LIG. Shock: A Review of Pathophysiology and Management. Part II. Critical Care and Resuscitation.