Maxillofacial Trauma

Combination of facial fractures and soft tissue damage that may be life-threatening due to:

- Haemorrhage

- Airway compromise

- Bleeding

- Oedema

- Can be massive and cause significant distortion

- Generally evolves over 24-48 hours

- Association with significant intracranial injury

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Associated with:

- Young

Predominantly 15-25. - Male

- Alcohol

Pathophysiology

Mandibular fractures:

- Commonly occur at structurally vulnerable sites, independent of point of impact

- Condyles

May limit mouth opening, even after muscle relaxation. - Symphysis

Point of midline fusion. - Angle

- Condyles

- Multiple fractures are common

Mid-face fractures:

The midface acts similarly to a crumple zone on a car and collapses progressively under impact. Multiple complex facial fractures are therefore the most common presentation.

- Facial skeleton consists of several small compartments supported by three vertical buttresses

- Compartments:

- Orbits

- Nasal cavities

- Paranasal sinuses

- Buttresses:

- Nasomaxillary pillars

- Zygomaticomaxillary pillars

- Pterygomaxillary pillars

- Compartments:

- Fracture-dislocations occur as the facial skeleton collapses around these pillars

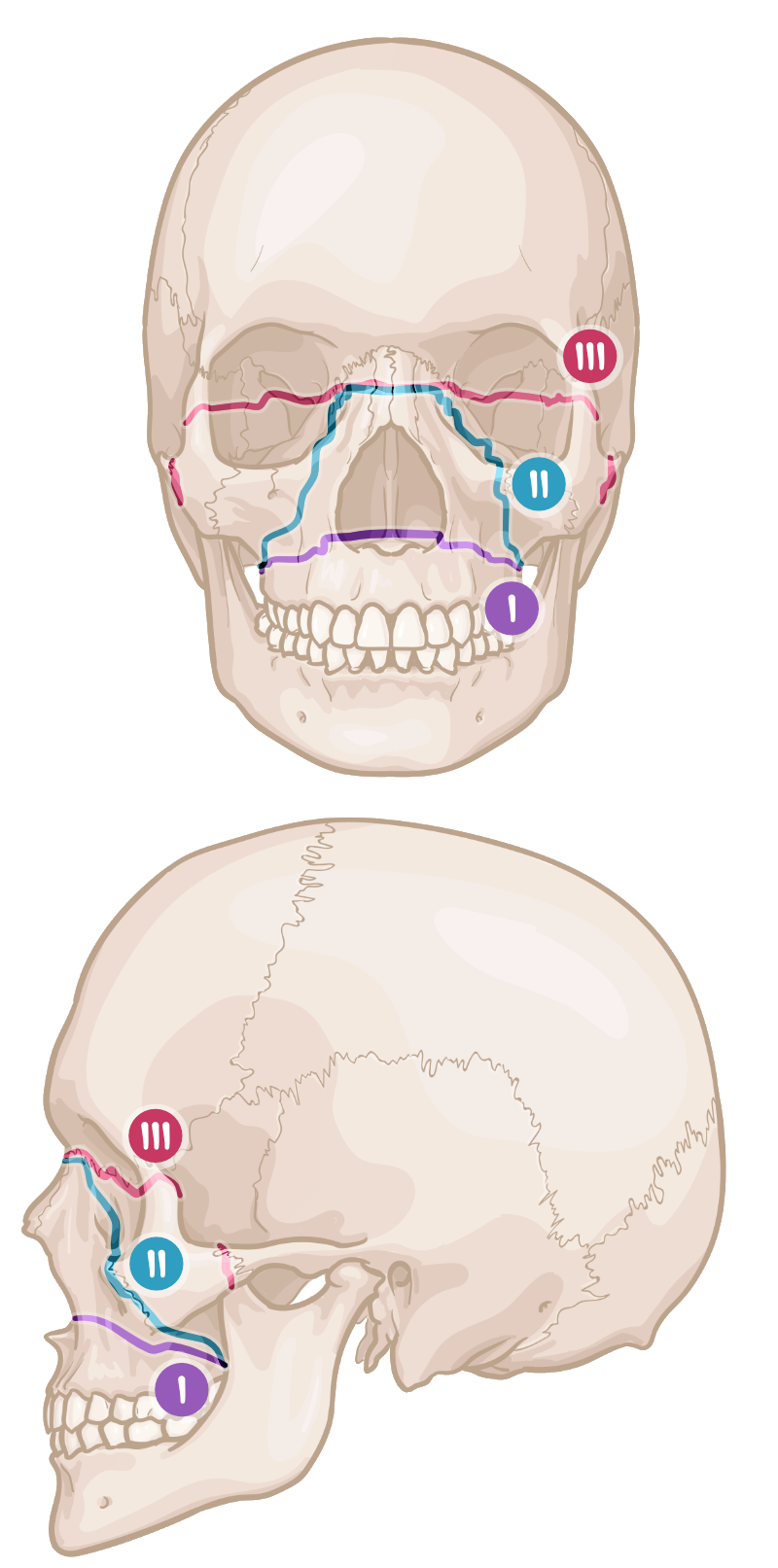

Occurs in a predictable fashion, giving rise to the Le Fort classification:- Le Fort I

Horizontal fracture of the maxilla at the plane of the nose.- Direct maxillary impact

- Le Fort II

Freely mobile pyramid of maxilla.- Most common fracture

- Inferior or lateral mandibular impact with a closed mouth

- Le fort III

Separation of midface from the base of the skull.- Also known as craniofacial disjunction

- May result in cribiform plate transection and CSF leak

- Le Fort I

Orbital fractures:

- Inferior orbital wall fracture most common

Direct pressure on globe is transmitted back to the orbit, with the weakest wall shattering. - May result in entrapment of globe or extra-ocular muscles

- Loss of visual acuity

- Abnormal eye movements

Aetiology

Facial injures are almost all related to blunt trauma; common causes include:

- MVA

- Assault

- Falls

- Sport

- Industrial accidents

Clinical Manifestations

Evaluation should include:

- Visible deformity

- Asymmetry

- Nasal septal deviation

- Fracture stability

- Palpation of midface for mobile segments

- Dental malocclusion

- Visual assessment

- Visual acuity

- Pupillary reflexes

- Eye movements

- Cranial nerve function

- Facial nerve

- Evidence of base of skull fracture

- Enopthalmos

Retraction of the eye due to blowout fracture. Upward gaze is usually impaired. - Bleeding

- Haemotympanum

- Battle’s sign

- Raccoon eyes

- Enopthalmos

- Orbital bruit

Suggests carotid-cavernous sinus fistulae.

Diagnostic Approach and DDx

Investigations

Bedside:

Laboratory:

Imaging:

Other:

Management

Airway management can be complex due to interplay of:

- Trauma

With effect of other injuries. - Oedema

- Haemorrhage

- Aspiration

- Impaired topicalisation

- Impaired

Resuscitation:

This details management of isolated midface injuries and implies reasonably normal laryngeal and tracheal anatomy.

Laryngotracheal trauma is rarer, and:

- Evidenced by stridor or hoarseness with overlying neck abnormalities

- Requires complex airway management strategies

- Covered under Laryngotracheal Trauma

- A

- Basic interventions

- Head-up position

Patient may assume unusual positions that limit obstruction, this should be encouraged. - High flow oxygen

- Regular suctioning

- Head-up position

- Advanced airway management

Planning should include senior airway clinicians. Considerations include:- Bag-mask ventilation often difficult

- Limited mask seal

- Pain

- Fibre-optic nasal intubation for mandibular condyle fracture with limited mouth opening, without base of skull fractures

- Non-condylar mandibular fractures are mobile when pain is controlled

- Awake oral fibre-optic intubation for:

- Cervical spine injury

- Mandibular condyle and base of skull fracture

- Awake tracheostomy may be considered

- Bag-mask ventilation often difficult

- Basic interventions

- C

- Bleeding

- Direct pressure

- Aggressive packing to wounds and nasal cavities

- Bleeding

Peculiar interventions that may assist airway patency include:

- Tongue protraction

Suture through anterior tongue allows tongue to be pulled forwards. - Midface protraction

Anterior traction of the mobile midface may relieve obstruction but ↑↑ venous bleeding.

Specific therapy:

- Pharmacological

- Prophylactic antibiotics

For CSF leak.

- Prophylactic antibiotics

- Procedural

- Angioembolisation

1st line for intractable bleeding. - Surgical haemorrhage control

- Debridement and washout

Within 24 hours. - Internal fixation

Often delayed 4-10 days until swelling has resolved.

- Angioembolisation

- Physical

Supportive care:

Disposition:

Preventative:

Marginal and Ineffective Therapies

- Steroids

No role in optic nerve injuyr.

Anaesthetic Considerations

Complications

Facial fractures have several associated injuries:

- A

- Dental injury

- C

- Carotid-cavernous sinus fistula

- D

- Cervical spine injury

- Intracranial injury

- Orbital injury

Vision loss or blindness in ~1%. - Base of skull fracture

- CSF leak

- Occurs in 10-30%.

- May present with either:

- Rhinorrhoea

- Otorrhoea

- Meningitis uncommon despite the prevalance of CSF leak

- CSF leak

Bones that may result in dural tears and CSF leak include:

- Frontal bone

- Frontal sinus

- Nasoethmoid complex

- Fronto-orbital complex

Prognosis

Key Studies

References

- Bersten, A. D., & Handy, J. M. (2018). Oh’s Intensive Care Manual. Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.